What's Israel's Real Beef with UNRWA?

UNRWA is a source of hope for all Palestinians, which is why Israel wants to destroy it

The Israeli Knesset passed two major bills Monday banning the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) from operating across Israel and its occupied territories, including East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza.

This is a devastating blow to the agency that’s been providing essential aid to Palestinians for decades, especially during the last year during which Israel has severely restricted humanitarian aid to the over two million Palestinians trapped inside Gaza while it attacks them from the skys above.

A second bill, passing 87-9, goes further, banning Israeli authorities from any coordination with UNRWA.

Without that coordination, UNRWA's work in Gaza and the West Bank is effectively cut off, as Jerusalem will no longer issue entrance permits or allow access through IDF checkpoints. Israel also controls Gaza’s access to Egypt, with the IDF stationed along the Gaza-Egypt Philadelphi Corridor. Times of Israel

The UN and seven of Israel's closest allies responded with strong condemnation, warning that this decision could have “devastating consequences on an already critical and rapidly deteriorating humanitarian situation, particularly in northern Gaza.” Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, and the UK all signed on.

UNRWA Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini called the move a clear violation of the UN Charter and Israel’s obligations under international law. UN Secretary-General António Guterres added that the outcome could be catastrophic.

The vote by the Israeli Parliament (Knesset) against @UNRWA this evening is unprecedented and sets a dangerous precedent. It opposes the UN Charter and violates the State of Israel’s obligations under international law.

— Philippe Lazzarini (@UNLazzarini) October 28, 2024

This is the latest in the ongoing campaign to discredit…

The vote by the Israeli Parliament against @UNRWA is unprecedented. It opposes the @UN Charter and violates the State of Israel’s obligations under international law.

— UNRWA (@UNRWA) October 28, 2024

Failing to push back against these bills will weaken our common multilateral mechanism.

This should be a… https://t.co/kx5JJOVEGe

U.S. State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller weighed in, calling for Israel to reconsider:

"We urge the Israeli government to pause the implementation ... if UNRWA doesn't exist, civilians, including children and babies, will not get the food they need, and this is for us unacceptable.” - Matthew Miller

State spokesman Miller urges Israel to “pause implementation” of Knesset legislation banning UNRWA, highlighting its “irreplaceable role in Gaza.” He warns that it “could have implications under U.S. law,” and the administration “will consider next steps based on what happens in… pic.twitter.com/x6znS9FZNd

— Drop Site (@DropSiteNews) October 28, 2024

Meanwhile, Knesset member Yulia Malinovsky claimed that U.S. Ambassador to Israel Jacob Lew had even tried lobbying other Israeli lawmakers to vote down the bill:

“UNRWA colluded with Hamas, it is educating kids to hate Israel and spreading antisemitism, it is selling them stories that they will be able to come back to Israel. This will not happen,” Malinovsky said. (CNN)

What’s Israel’s Problem with UNRWA?

UNRWA has been a fixture in Palestinian lives since 1950. Its role, politically and practically, is so vital to Palestinians that it’s exactly why Israel wants it gone.

UNRWA was created in 1949 and began operating the next year, a few years after WWII, and as a condition for Israel’s entry into the UN. The agency’s mission? To assist over 750,000 Palestinians who were forcibly displaced to create the state of Israel, an event known as the Nakba, or “catastrophe.”

For a long time, Israel saw value in keeping UNRWA around—it offered stability in the occupied territories and relieved Israel of some of its obligations as the occupying power. UNRWA’s support in areas like healthcare, food, and education helped prevent chaos and uprisings, making it a convenient way for Israel to keep upheaval contained.

But now, amid their brutal assault on Gaza, Israel sees UNRWA as a barrier to its goal of breaking the Palestinian will entirely.

“They dislike the agency’s symbolism for precisely the reason that it resonates with Palestinians. They believe UNRWA to be harmful to Israeli interests by keeping alive the notion that Palestinians could return one day to live in Israel, which they believe is incompatible with preserving Israel as a Jewish state.” —Crisis Group

And Israel hasn’t just stood by. It has actively worked to dismantle UNRWA.

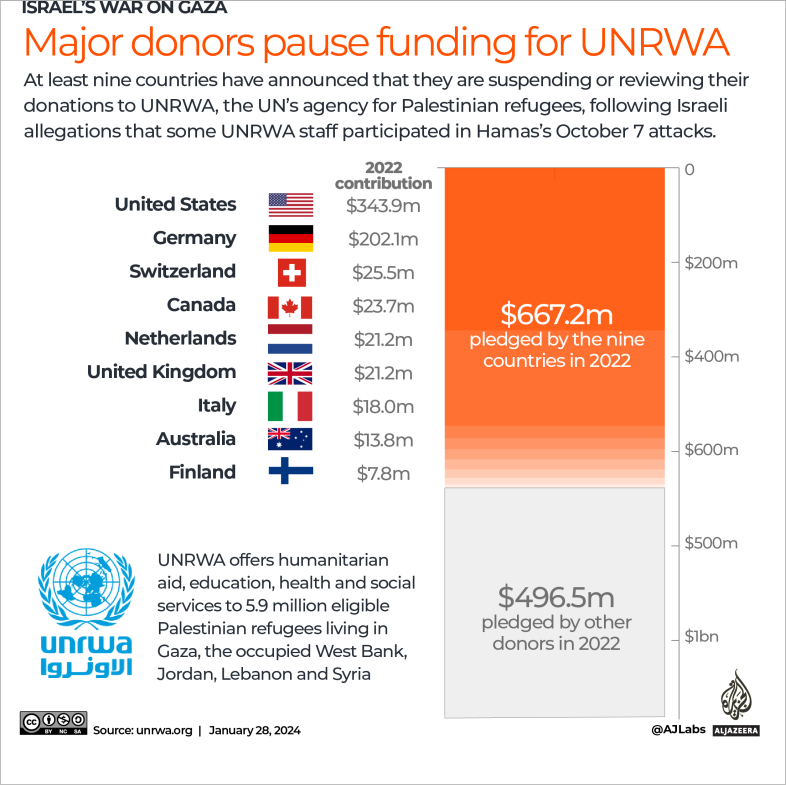

Earlier this year, Israeli officials accused UNRWA employees of being involved in the October 7 attacks. This accusation led countries—including the U.S.—to temporarily pull funding, threatening UNRWA’s ability to deliver basic services to two million Gazans who are now facing dire humanitarian conditions. Ten months later, Israel has yet to provide any evidence of their claims.

UNRWA strongly denied these accusations, insisting on the neutrality of its staff:

UNRWA says it insists on the neutrality of its staff and said the allegations made by Israel about 66 employees out of 30,000 staff amounted to just 0.22% of its payroll. (CNN)

After multiple internal and external UN investigations found zero evidence for the allegations, many of those countries restored funding to UNRWA. And this only renewed Israel’s issue with the agency.

Israel’s Arguments Against UNRWA

So, what are Israel’s arguments for why UNRWA shouldn’t exist?

Israel says Palestinians shouldn’t have a special agency. Instead, they should fall under the broader UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) like other refugees. But, as award-winning journalist Jonathan Cook notes, this separation wasn’t a Palestinian request.

“Although Israel does not want you to know it, the reason for there being two UN refugee agencies is because Israel and its western backers insisted on the division back in 1948. Why? Because Israel was afraid of the Palestinians falling under the responsibility of the UNHCR’s forerunner, the International Refugee Organisation. The IRO was established in the immediate wake of the Second World War in large part to cope with the millions of European Jews fleeing Nazi atrocities.”

“Israel did not want the two cases treated as comparable, because it was pushing hard for Jewish refugees to be settled on lands from which it had just expelled Palestinians. Part of the IRO’s mission was to seek the repatriation of European Jews. Israel was worried that very principle might be used both to deny it the Jews it wanted to colonise Palestinian land and to force it to allow the Palestinian refugees to return to their former homes. So in a real sense, UNRWA is Israel’s creature: it was set up to keep the Palestinians a case apart, an anomaly.” —Jonathan Cook

For Palestinians, UNRWA is more than just an agency. It’s a safeguard for their “right to return,” a guarantee that their displaced status is temporary. Without UNRWA, Palestinians’ identity as refugees fades, and their connection to their homeland starts to feel more like a lost cause.

“In the Palestinian consciousness, as long as UNRWA exists as a temporary international mechanism, which has now survived for 75 years, a Palestinian refugee has the right to return to his homeland. If UNRWA goes, his own status is no longer temporary but becomes permanent.” —Crisis Group

UNRWA registers not only original Palestinian refugees but their descendants, too. Israel sees this as an escalating issue because the number of Palestinians with the “refugee” label grows over time, keeping the return claim active.

And it’s worth noting that this isn’t unique to Palestinians. The UNHCR also allows descendants of refugees from Rwanda and Kosovo—countries where genocides have occurred—to keep their refugee status.

“Israel insists that no other refugees in other places in the world make similar multigenerational claims. For Palestinians, however, the right of return is a gold standard. Acknowledgment of the Nakba and the right to go back to the land of their parents and grandparents is tantamount to recognition of Palestinian national identity. Palestinians have argued their claim based on international law and historic justice.” —The Century Foundation

"In 1949, Israel passed a law permitting Jews from anywhere in the world—with no previous connection to the land—to 'return' and acquire full citizenship upon entry. It simultaneously established a shoot-to-kill policy for Palestinians trying to return to their homes... Since its establishment, Israel has equated the return of Palestinian refugees with its destruction. Not because of capacity or security, but because the return of Palestinians would undermine a myth of uninterrupted Jewish presence in Palestine and, more importantly, a Jewish demographic majority achieved through ethnic cleansing and maintained through racist bureaucracy.” —Noura Erakat, Washington Post

What Happens If There’s No UNRWA?

Losing UNRWA isn’t just symbolic—it would mean Palestinians lose critical support:

UNRWA doesn’t resettle refugees but rather supports them in exile. It provides food, healthcare, and other social services, employing around 30,000 people in Gaza—where joblessness is at crisis levels due to Israeli-imposed restrictions.

UNRWA schools teach Palestinian history, human rights, and the lived experiences of refugees. While Israel accuses UNRWA schools of teaching hatred, Palestinian educators emphasize these schools teach students about human rights advocacy and self-determination.

There are nearly six million Palestinian refugees across Gaza, the West Bank, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, with around 1.5 million living in refugee camps. UNRWA is the one agency bridging these communities across borders.

At its core, UNRWA was created as a temporary solution until Palestinians could return home. It is the thread that connects Palestinians to their homeland from which they were displaced and where they continue to be persecuted. By destroying UNRWA, Israel hopes Palestinians will accept a future in which they no longer have a right to return.